THIS EPISODE COVERS THE YELLOW CLEARANCE BLACK BOX BLUES, a classic 1985 adventure for Paranoia by John M. Ford.

“Elephant detected!” – James

- See the Wikipedia entry for The Yellow Clearance Black Box Blues

- See The Yellow Clearance Black Box Blues at DriveThruRPG

- Learn more about Paranoia at DriveThruRPG

- See John M. Ford’s page on Wikipedia

This episode is brought to you with the help of Brownie, who wants to give a shout out to the excellent actual-play podcasts Technical Difficulties and The Roleplaying Exchange. We are very grateful to Brownie and all our listeners for their support.

>>>>>THE AUDIO FOR THIS EPISODE IS CURRENTLY ONLY AVAILABLE TO THE PODCAST’S BACKERS. WHEN IT GOES PUBLIC, THE LINK TO THE RECORDING WILL APPEAR ON THIS PAGE.

>>>>>TO GET EARLY ACCESS, YOU CAN BECOME A SEASON 3 BACKER FOR JUST $20 BY CLICKING HERE

SHOW NOTES

These are the show notes for the episode, where we delve further into things that we don’t have time to explore in detail in the podcast itself, festooned with links for your rabbit-holing pleasure.

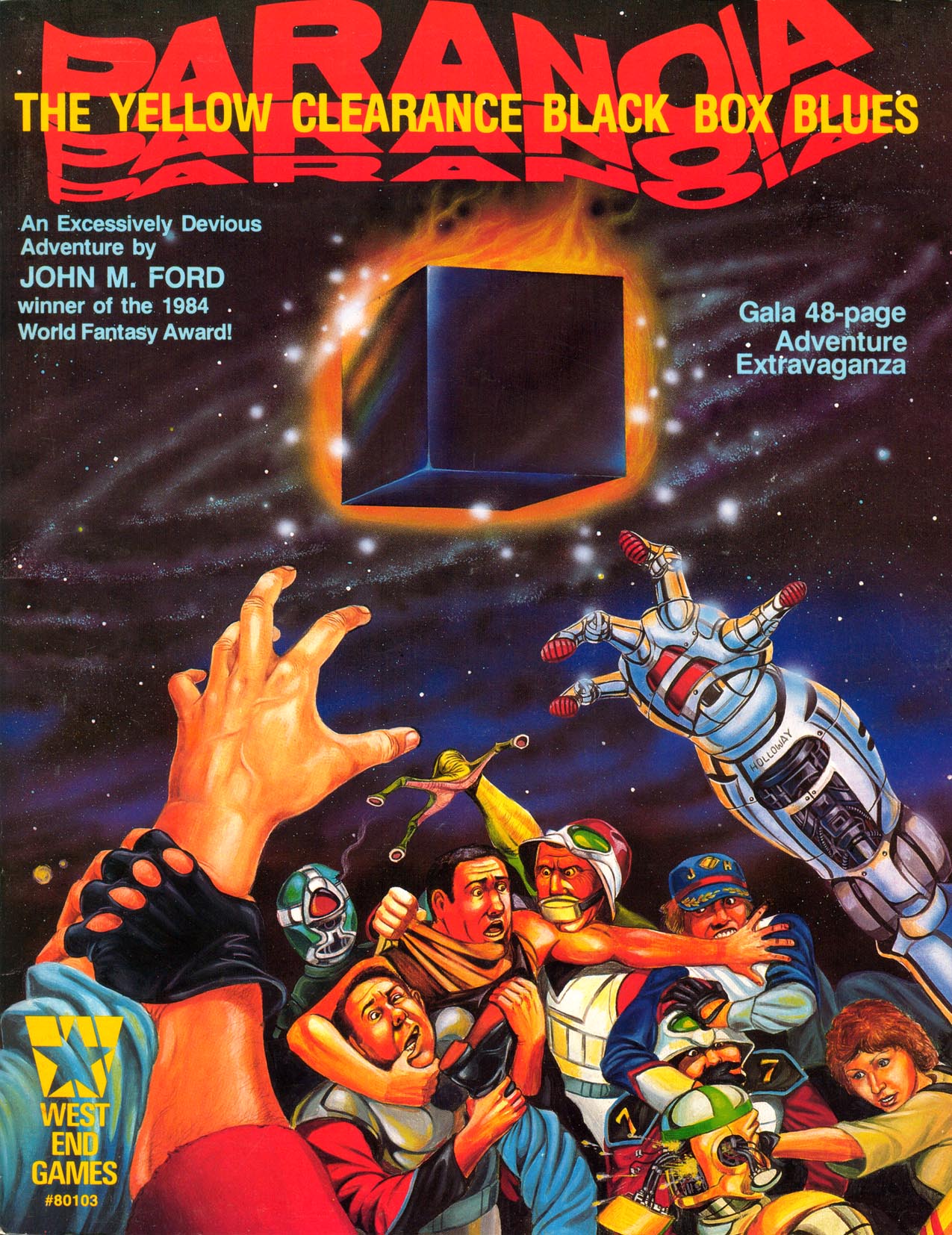

The Yellow Clearance Black Box Blues is a 48-page adventure for the Paranoia RPG. It was written by John M. Ford, published by West End Games in 1985, and is generally regarded as one of the classic adventures for the game, as well as a milestone in the development of comedy in RPGs. It was re-released in 2017 for the rebooted edition of Paranoia that was co-designed by James Wallis, Grant Howitt and Paul Dean, and I swear that’s the first I’ve ever heard of that version, though it seems to be the only form in which TYCBBB is commercially available right now. $29.99 for a 48-page PDF from 1985, fuck me, you’d think this was academic publishing or something.

Paranoia was created by Dan Gelber, Greg Costikyan and Eric Goldberg, and published in 1984 as part of the golden age of West End Games. This lasted 1984–1989 when WEG was the most exciting adventure games company in the world, producing the Ghostbusters RPG, the original Star Wars RPG, the genre-defining narrative board game Tales of the Arabian Nights, and more. Paranoia has been in print almost continuously ever since. If you don’t know its setting, we go into that a bit in the podcast.

In the episode James says he thinks that Dan Gelber, original Paranoia creator, has died. This is incorrect. James checked with Greg Costikyan (because that’s how LND does things) and as far as he knows Dan is still alive.

As an author John M. Ford will mostly be remembered for creating Klingons as we understand them today: years before Star Wars authors were told to use RPG books for research, his 1983 The Klingons sourcebook for FASA’s Star Trek RPG laid the foundation for the modern version of the knobbly starfarers. The same year he wrote The Dragon Waiting, an alt-history medieval tapestry that constantly wrong-foots the reader and won the World Fantasy Award. Ford died at his home in Minneapolis in 2006, aged 49, and is sadly missed.

Jim Holloway’s art defined the first and second editions of Paranoia, but he was also a prolific artist for TSR and Mechwarrior in the 1980s. Since his death in 2020 his websites have mostly rotted but you can get a sense of the man and his work here.

As we mention in the podcast, Paranoia is a time-capsule of attitudes from the mid-1980s, specifically from the USA in the mid-1980s, and a lot of its referential humour has aged badly (for example the Sierra Club was and is an organisation entirely unknown to non-Americans). As someone reading it at the time, it was sometimes hard to know what was parody and what was just a reflection of American culture. Still is.

Movies the game uses as touchstones: THX 1138 was George Lucas’s first full-length movie, based on a film he made as a student, and co-written with the great Walter Murch. Set in an underground bunker city, it follows the monotonous and regimented life of THX 1138, played by a young Robert Duvall (note that Paranoia characters have names in the format Bill-Y-BOT-6) until he stops taking his required drugs and rebels. Its world-building is better than its rather simple story, which doesn’t explain why Lucas, in the throes of his early-2000s obsession with CG, ruined the 2004 Special Edition by adding ‘windows’ to every vertical surface in the original, thus spoiling the claustrophobia of the original, and the last-reel reveal that the city is underground. (I firmly believe that Lucas has never understood what made the original Star Wars so good, and has spent the rest of his career trying to work it out.)

Terry Gilliam’s Brazil is a retro-futurist story set in a dystopian world where almost everyone works for the Ministry of Information. It’s a heady blend of 1984, Kafka, and Fellini’s 8½. Paranoia‘s love of pointless bureaucracy and paperwork overlaps hard with Brazil, though it was a theme prevalent in British humorous SF at the time, particularly The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Brazil wasn’t actually released until 1985 and so can’t have been an influence on Paranoia, but both reflect themes and tones that geeks in the mid-1980s would have recognised.

We also mention Airplane! (1980) and Airplane II: The Sequel (1982), the Zucker Brothers’ epoch-defining deconstructions of the disaster movie genre, and movies generally. That style of humour, of laying joke over joke over joke so you still haven’t drawn breath from laughing at the last punchline by the time the next one hits, is incredibly hard to do in RPGs and TYCBBB wisely doesn’t try, though Ford’s use of running gags and staggered callbacks works to build the game-humour nicely, even if much of it is in read-aloud text sections.

Reference comedy is a style of alleged humour where the joke comes from recognising a familiar reference in another context. Often that’s all there is to it. World of Warcraft used to use it a lot, and the early-2000s Keenen Wayans movies, starting with Scary Movie, were basically built on it. It’s easy and lazy, which doesn’t mean that it can’t be funny, but particularly in an RPG it needs more than “Here’s a character from a popular advertisement but now they’re in a dungeon with an axe!” It makes a vague kind of sense in TYCBBB, things left over from the present day would be around in Outside, and allowances have to be made for the fact it was the 1980s, still a few years out from the Decade of Irony that ruined everything.

Berserk, which Greg referred to, was a 1980 arcade game manufactured by Stern. The protagonist is a human with a gun in a maze, where a small number of slow robots pursue and shoot at him. Sometimes they shoot each other by mistake. If the human takes too long to leave the maze (revealing more maze), a smiley face called Evil Otto appears and kills him. It was one of the first games to use synthesised speech, and one of the first in a dungeon-like setting.

‘The Fantasy Explosion video’, properly titled Youth Probe Presents: The Fantasy Explosion from 1985, is 35 minutes of heady Satanic Panic hysteria, tackling “How you and your family are being exploited by: pornography & teenage sex films, music videos, occult films, toys, soap operas & romantic novels, role-playing games, and comic books”. Gosh.

Collaborative worldbuilding: if you didn’t catch it, here’s the section of text James read out: “On the other hand, some players think you are responsible for perfect knowledge about your setting. These folks are in for a rude awakening in the world of Paranoia. If they keep bugging you about details and contradictions in your descriptions, their characters should have special accidents that make it hard for them to perceive their environments…. Batter their PCs a little, then given them a second chance to cooperate in building the setting rather than chiselling at it for tactical advantages. Privately remind wargaming and competitive players that Stalingrad and chess are still commercially available, but that tonight you are playing Paranoia.”

Once again, this is from 1985.

The Paranoia security clearances, for those who don’t know the game, run from Infrared, the lowest of the low, through the seven colours of the visible spectrum up to Ultraviolet, the High Programmers. Player characters typically start at Red, and by the standards of the original edition of the game Yellow clearance (as in the title of the adventure) is quite advanced.

Everway was the RPG Jonathan Tweet designed after Over the Edge. It was released in 1995 by Wizards of the Coast, flush with Magic the Gathering profits, as a deluxe boxed set with large-format art cards painted by notable fantasy artists, which were used as prompts, story guides and randomisers in character generation and roleplay. Critically praised but commercially unsuccessful – for many reasons – it is available from a new publisher in a revised edition.

A list of RPGs that Games Workshop published in UK editions under licence between 1977 and 1987: Dungeons & Dragons; Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (PHB and MM, plus some modules); Traveller; Runequest 2e and 3e; Star Trek the RPG 2e; Paranoia 1e and 2e; Call of Cthulhu 2e and 3e; Middle-earth Roleplay; Stormbringer 3e. If I’ve missed any, please let me know.

The Ghostbusters RPG is relevant to this discussion because it was published by West End two years after Paranoia came out, having been edited/rewritten (depending on who you talk to) by Greg Costikyan. It melds a genre-appropriate simple system that encourages creative play with a structure that works to let players be funny without being comedians or resorting to reference comedy. It is rare and collectible. LND listener Jonas Schiött pointed us at a retro-clone system, Spooktacular, which at first glance seems to have made the same mistake that Ghostbusters International (essentially a revised second edition) did in 1989: adding more rules.

Zip-a-Tone was a trademarked form of Screentone, a pre-digital way of adding shading to artwork. It was available in multiple graphic styles: fine dot screens, hashes, lines and others. Two versions existed: rub-down dry transfers, and adhesive sheets that could be cut to size.

Barks are short exclamations or sayings from video-game dialogue, designed to be used repeatedly in different scenes. Of course, a character can’t just shout ‘Grenade!’ the same way every time, that would spoil the suspension of disbelief that the game has lovingly built up (despite health-packs, respawning and all the other things that games do and real world fights don’t), so coming up with ten different barks to tell the player there’s a grenade/ogre/truck/end-of-the-world coming their way is a rite of passage for junior game writers, and senior game writers, and quite a lot of narrative designers too.

Cory Doctorow’s reworking of Poe’s ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ is also called Masque of the Red Death.

The concept of Outside has also been used in Fallout, Silo, Paradise and Zardoz, but all of those work with the protagonists starting inside but knowing that Outside exists, at least in theory, even if they believe it will kill you. In Paranoia, as in THX 1138, the protagonists don’t know there’s anything beyond the complex.

Mirror World exists.

3:16 Carnage Among the Stars by Gregor Hutton is a huge game in a small book. Depending on your point of view it’s either a strategy board game with some role-playing elements, or a roleplaying game that happens to use a strategy boardgame as its main mechanic. Either way it does some genuinely brilliant things with storytelling systems, including flashbacks and promotions (not the same as levels), and if you can’t quite bring yourself to buy the Warhammer 40K RPG then trust me, this will do just as well, if not better.

3:16 Carnage Among the Stars by Gregor Hutton is a huge game in a small book. Depending on your point of view it’s either a strategy board game with some role-playing elements, or a roleplaying game that happens to use a strategy boardgame as its main mechanic. Either way it does some genuinely brilliant things with storytelling systems, including flashbacks and promotions (not the same as levels), and if you can’t quite bring yourself to buy the Warhammer 40K RPG then trust me, this will do just as well, if not better.

Sealab 2021 was a Cartoon Network/Adult Swim series that reused footage from the 1972 Hanna Barbera cartoon Sealab 2020, re-edited and with a new script, to parody the original and the conventions of many other cheaply animated shows from the 1970s. It ran for four seasons, 2000–2005. It’s worth noting that the original Sealab 2020 was devised by comics legend Alex Toth, who also created Space Ghost. Many of the comics greats also worked in TV animation: there was a period in the 1980s when Jack Kirby, Gil Kane and Jim Woodring were all working at Ruby Spears, and one day I will write a novel about the animated series that in a perfect alternate world they collaborated on.

(Kane and Kirby did co-create the Ruby Spears series The Centurions (1986). There is a board game based on it. It is very bad.)

Harvey and Elwood: Harvey is the titular character of the 1950 movie Harvey starring James Stewart as Elwood P. Dowd, an amiable eccentric whose best friend is an invisible man-sized rabbit. It has rather fallen out of circulation in the C21st which is a shame as it’s a delightful good time, and worthy of a place in the canon of greats purely for the line ‘Years ago my mother used to say to me, she’d say, “In this world, Elwood, you must be” – she always called me Elwood – “In this world, Elwood, you must be oh so smart or oh so pleasant.” Well, for years I was smart. I recommend pleasant.’

Jake and Elwood Blues are, of course, the Blues Brothers, and are generally unconnected with any giant rabbits, though it’s an easy mistake to make.

A Macguffin – you think you know this one but stick with it, this is good stuff. Hitchcock popularised the term but it was actually coined by his regular collaborator, screenwriter Angus MacPhail (Went The Day Well? and Whiskey Galore!) for a desired object that drives the plot without actually affecting it. The actual nature of the item is unimportant to the story. Examples include the Golden Fleece, the Holy Grail in both the Arthurian cycle and Indiana Jones 3, the Maltese Falcon, the briefcase in Pulp Fiction, and arguably the One Ring. Earlier, silent movie star Pearl White had used the term ‘weenie’ to describe whatever the macguffin of that episode of The Perils of Pauline was. Andrew Rilstone used to call any blatant macguffin in the fantasy genre a ‘magic football’; multipart versions (“You must collect the five parts of the Staff of Macguffin”) are ‘plot coupons’, ‘plot tokens’ or a ‘dismantled macguffin’. French filmmaker Yves Lavandier argues that true macguffins only motivate villains: the protagonists are drawn into their narra-gravitational field for other reasons, and so it follows that if your characters are following a macguffin then perhaps they should look closely at their motivations and alignment.

And we’ll take any excuse to mock the Shadowrun video ‘A Night’s Work’ again.

Thank you for listening! The hosts of this episode were Ross Payton, Greg Stolze and James Wallis, with audio editing by Ross and show notes by James. We hope you enjoyed it. If anything in this episode has spurred your interest then we invite you to come and discuss it on our Discord.

If you click on any of the above links to DriveThruRPG and buy something, Ludonarrative Dissidents will receive a small affiliate fee. You will not be charged more, and the game’s publisher will not receive less, it’s a win-win-win. Thank you for supporting the podcast this way.